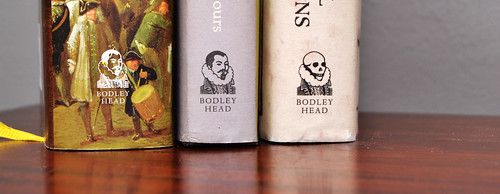

Graham Greene, following an argument with Anthony Powell over delays in the publication of his

John Aubrey and His Friends on the part of Greene's firm, Eyre & Spottiswoode, famously called Powell's biography "a bloody boring book."

He's not entirely wrong. The life of Aubrey offers an irresistible opportunity for Powell to indulge in two of his favorite pastimes, heraldry and genealogy. And while, given what we know from his fiction of how he saw the structures of society and their relation to the individual, it's easy to understand why

he finds the two subjects of such interest, it's hard for the rest of us to work up a similar enthusiasm, especially when it comes to minor cousins and manservants of little-known acquaintances of Aubrey. (To be fair, such attention to peripheral matters does occasionally pay off, as when Powell points out that the offer of a favor from a fourth cousin, once removed, "is a good illustration of seventeenth-century acceptance of remote family ties.")

Add in the fact that Aubrey's life has to be reconstructed from a small, quite messy amount of source material--in his biography of Powell, Michael Barber points out that

the few scraps of autobiography he completed were prefaced by the instruction that they should be interposed "as a sheet of wast paper only in the binding of a book"

--and that the unsettledness of seventeenth-century English life around the Civil War makes parsing people's social, religious, and political positions both essential and difficult, and you've got a recipe for, well, a "bloody boring book."

Ah, but it's Powell, and it's Aubrey, and just often enough, throughout the book, there is a moment that makes it all worth the trouble. It's easy to see why Powell chose Aubrey as a subject: they share a catholic interest in every facet of human behavior and the stories they generate. Especially the odd ones. Aubrey's life work was the lives of others, and even in his own biography he takes a back seat regularly to the stories of those around him, Nick Jenkins–style. We get the occasional ever-so-Powellian observation, like this, from his explanation of how Aubrey and the prickly Oxford antiquarian Anthony Wood (who was "at odds with almost everyone with whom he came in contact"

*) were able to maintain a friendship for decades despite being of wildly different temperaments: It was because of their

unworldliness, a quality whose various forms can bind into some sort of affinity widely divergent types of men.

Sady, unworldliness could only do so much, and once they fell out, Wood blasted Aubrey as

a shiftless person, roving & magotie-headed & sometimes little better than crazed.

We also get a memorable line on the academy, which Powell, though never truly a scholar, was astute in assessing: It is plagued by

those uninviting pedants who at any period form a scarcely avoidable ingredient of academic life.

Then there's Powell, who wouldn't turn diarist until late in life, pointing out the problem with Anthony Wood's otherwise quite useful diaries: Wood, he fears, fell victim to

the besetting frailty of the diarist, that is to say "touching-up" passages at a date later than that of the original entry.

Ultimately, however, it's Powell's liberal use of quotation from the letters of Aubrey and others that bring Aubrey, the book, and the seventeenth-century world, to life. Take this letter, from November 28, 1671, from Aubrey to Wood, on the perpetually difficult theme of Aubrey's family:

I have a great desire to see my honest brother Tom well settled, marryed to a good discreet wife with about 800li or 1000li which his estate (Chalke farme 250li per annum) does very well deserve. I wish you could find [such] another as your sister-in-law or neice if she were big enough. My great-grandmother was of Oxfordshire: and I like the people mighty well. About Chalke are no wives nearer than Salisbury, prowd and all gamesters, and unknowing or unfit for a country gent., turne and in North Wilts they will be drunken. Is it not an odd thing to send to a monk and an antiquary about such a question, but how can I tell what may happen. Some of your acquaintances may hint.

Troubles of that sort were never far from Aubrey, who lived the last half of his life as a roving guest in the country homes of friends and patrons, often living secretly to hide from his creditors. As he writes in another letter, "New troubles arise from me like Hydra's heads," and

This yeare all my businesses and affaires ran kim kam. Nothing took effect, as if I had been under an ill tongue.

In a letter to Wood, he tells of putting his books in a trunk,

but dare not trust my brother with the key, for my books would be like butter-flies, and fly about all the country.

In a later letter to Wood, he worries about the fate of his papers, which he has given to Elias Ashmole for eventual deposit in the new museum Ashmole was founding in Oxford:

My heart is almost broke and I have much adoe to keep up my poore spirits. . . . I sent 4 or 5 yeares since (upon the threatening of my brother to throw me into Gaole [to avoid it himself, for debt]) those Things to Mr Ashmole in a Deale-Box, which was bigger than the thing required: but about a yeare since Mr Ashmole had occasion for a Box of that bignes, and tumbled out my things into that lesser box I sent downe: but I find it like a transfusion of Chymicall Spirits out of one glass into another, they wast by it: and some papers I am sure are miscarried. . . . all my Bookes at Mr Kent's; so that if I had leisure I cannot enjoy them.

As someone who at one point had most of his books packed up for a year in vain service to the gods of real estate, I sympathize deeply.

The letters are also full of dashed-off notes of encounters and marvels, as when in Orleans Aubrey met, writes Powell, "a young man whose left cheek had been gnawed by a werewolf." Aubrey explains that the man knew it had been a werewolf,

for, he sayd, had it been a wolfe he would have killed me outright and eaten me up.

On hearing music coming from a French church, he comments that

the French have much better, stronger, and clearer voices than the English.

Of clothiers, he remarks,

They steal hedges, spoil coppices, and are trained up as nurseries of sedition and rebellion.

Wandering London, he saw oddities:

On the day of St John the Baptist, 1694, I accidentally was walking in the pasture behind Montague House. It was 12 o'clock. I sawe there about two or three and twenty young women, most of them well habited, on their knees very busy, as if they had been weeding. I could not presently learn what the matter was. At last a young man told me that they were looking for a coal under the root of a plantain, to put under their head that night, and they should dream who should be their husbands. It was to be sought for that day and hour.

Alas, aspiring brides: that pasture now is covered by the British Museum; I fear your future husbands have flown.

Ultimately, however, it is as much Aubrey's relationship to time as it is his love of oddity and anecdote that makes him such a good subject for Powell. As Powell wrote in an introduction to a 1976 edition of Aubrey's

Brief Lives published by the Folio Society,

He was there to watch and to record, and the present must become the past, even though only the immediate past, before it could wholly command his attention.

We can't help but tell our stories from the moving train, with all the distortions and biases that entails. But the genius of Powell as a fiction writer and Aubrey as a chronicler lies largely in their preference for looking back a few cars, for giving people and events and anecdotes time to sort and settle and find their level. To allow time to help interpret, as time will.