An e-mail the other day from regular reader (and great writer) Lee Sandlin posed a question that seemed worthy of a quick post: Lee asked which author I had the most books by on my shelves--and, following that, whether that ranking reflected their actual position in my reading life?

I'll leave it to Lee to decide whether he wants to, in comments, reveal his top author, volumes-wise. For myself, I expected it would be Anthony Powell, which would be appropriate: as many of you know, Powell's books--not just the novels, but the volumes of collected reviews and occasional writings and his notebooks and journals as well--are ones I return to again and again, never tiring of his eye for character and appreciation of human oddity.

But Powell's 31 volumes, it turns out, are second . . . to Donald E. Westlake, who under his various writing names accounts for 36 volumes. Westlake is less influential than Powell on my writing and thinking day to day, but nonetheless there's rarely a day that goes by when I don't think about his books at some point. Iris Murdoch and P. G. Wodehouse take third with 28 apiece. The number of Wodehouse books is essentially unimportant: what matters is that they're all in some wonderful way the same and that there's a near-infinite supply of them. As for Murdoch: there was a time when she was easily my favorite writer, and while others have surpassed her, I still feel a thrill when I open one of her novels--the wildly emotional, comic world she creates is unlike anything else. Dickens comes next with a mere 25, yet another reason to curse the unhealthy strain of the reading tours that took him away from his desk for so many months!

And for you? Who leads the count on your shelves? Any surprises?

I've Been Reading Lately is what it sounds like. I spend most of my free time reading, and here's where I write about what I've read.

Monday, July 30, 2012

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

Courage, conviction, and the better world we dream of

On March 9, 1949, the newly elected junior senator from Texas, Lyndon B. Johnson, took the Senate floor to deliver his maiden speech. Running to thirty-five single-spaced pages, it argued vigorously against President Truman's proposed civil rights bill designed to end employment discrimination, ease voter registration, and offer federal protection against lynching. Robert Caro, in Master of the Senate, the third volume of his four-volume-and-counting biography of Johnson, offers a quote-heavy summary:

The greatest achievement of Caro's biography is that it allows us to simultaneously grasp that Johnson--seemingly irreedemable--and the Johnson who would, through his pushing through of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first successful civil rights bill in nearly a century, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, do more for black Americans, and for America's ideal of equality in general, than any elected official other than Lincoln. Caro makes a convincing case that no one but LBJ could have gotten those bills passed. Does the latter achievement outweigh the former disgrace? Yes, in my book, but good god, how that early speech burns despite.

By contrast, let's look at Caro's account of Hubert Humphrey's impassioned speech to the 1948 Democratic National Convention that won a civil rights plank in the party platform (and, in the process, had the salutary effect of driving out part of the segregationist old guard to form the short-lived Dixiecrat party):

For the real thing, we'll turn to Montgomery, Alabama on the night of January 30, 1956, during the Montgomery bus boycott. Reverend Martin Luther King was speaking at that evening's mass meeting at a church when word was brought to him that his house had been bombed. Taylor Branch, in Parting the Waters, describes King's response:

In the just world that King envisioned, Emmett Till would have been seventy-one today.

First, he defended the use of the filibuster. The strategy of civil rights advocates, he said, "calls for depriving one minority of its rights in order to extend rights to other minorities." The minority that would be deprived, he explained, was the South.It's hard to read this, to read Johnson's perversions of the concepts of "minority," "majority," "freedom," and--against the background of the 5,000 lynchings of black men and women that happened between the Civil War and 1960--"deadliest weapon" and not feel your stomach turn. This is one of the definitions of evil: to turn values on their head and enlist them in support of the opposite of their meaning, then to stand on pointless principle and thus condemn actual people to violence and death.

"We of the South who speak here are accused of prejudice," Lyndon Johnson said. "We are labeled in the folklore of American tradition as a prejudiced minority." But, he said, "prejudice is not a minority affliction: prejudice is most wicked and most harmful as a majority ailment, directed against minority groups." The present debate proved that, he said. "Prejudice, I think, has inflamed a majority outside the Senate against those of us who speak now, exaggerating the evil and intent of the filibuster. Until we are free of prejudice there will be a place in our system for the filibuster--for the filibuster is the last defense of reason, the sole defense of minorities who might be victimized by prejudice." "Unlimited debate is a check on rash action," he said, "an essential safeguard against executive authority"--"the keystone of all other freedoms." And therefore cloture--this cloture which "we of the South" were fighting--is "the deadliest weapon in the arsenal of parliamentary procedures." By using it, a majority can do as it wishes--"against this, a minority has no defense."

The greatest achievement of Caro's biography is that it allows us to simultaneously grasp that Johnson--seemingly irreedemable--and the Johnson who would, through his pushing through of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first successful civil rights bill in nearly a century, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, do more for black Americans, and for America's ideal of equality in general, than any elected official other than Lincoln. Caro makes a convincing case that no one but LBJ could have gotten those bills passed. Does the latter achievement outweigh the former disgrace? Yes, in my book, but good god, how that early speech burns despite.

By contrast, let's look at Caro's account of Hubert Humphrey's impassioned speech to the 1948 Democratic National Convention that won a civil rights plank in the party platform (and, in the process, had the salutary effect of driving out part of the segregationist old guard to form the short-lived Dixiecrat party):

For once his speech was short--only eight minutes long, in fact, only thirty-seven sentences.Humphrey's speech took conviction and courage, unquestionably, and he should be honored for that--but they were mere political conviction, political courage. Political courage gets praised frequently, in part because of its rarity, in part because we want to encourage it, and in part because reporters and columnists, enmeshed in a world where defeat in an election equates to death, confuse it with the real thing.

And by the time Hubert Humphrey was halfway through those sentences, his head tilted back, his jaw thrust out, his upraised right hand clenched into a fist, the audience was cheering every one--even before he reached the climax, and said, his voice ringing across the hall, "To those who say that we are rushing this issue of civil rights--I say to them, we are one hundred and seventy-two years late.

"To those who say this bill is an infringement on states' rights, I say this--the time has arrived in America. The time has arrived for the Democratic party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights."

"People," Hubert Humphrey cried, in a phrase that just burst out of him; it was not in the written text. "People! Human beings!--this is the issue of the twentieth century." "In these times of world economic, political and spiritual--above all, spiritual--crisis, we cannot and we must not turn back from the path so plainly before us. That path has already led us through many valleys of the shadows of death. Now is the time to recall those who were left on the path of American freedom. Our land is now, more than ever before, the last best hope on earth. I know that we can--know that we shall--begin here the fuller and richer realization of that hope--that promise--of a land where men are truly free and equal."

For the real thing, we'll turn to Montgomery, Alabama on the night of January 30, 1956, during the Montgomery bus boycott. Reverend Martin Luther King was speaking at that evening's mass meeting at a church when word was brought to him that his house had been bombed. Taylor Branch, in Parting the Waters, describes King's response:

"Are Coretta and the baby all right?"Caro describes the scene outside King's house when he arrived:

"We are checking on that now," said a miserable [Ralph] Abernathy, who had wanted to have the answer before telling King.

In shock, King remained calm, coasting almost automatically on the emotional overload of the past few days. Nodding to Abernathy and [S. S.] Seay, he walked back to the center of the church, told the crowd what had happened, told them he had to leave and that they should all go home quietly and peacefully, and then, leaving a few shrieks and a thousand gasps behind, walked swiftly out a side door of the church.

In front of King's home was a barricade of white policemen shouting to a huge crowd, a black crowd, to disperse, but the men in the crowd, yelling in rage, were brandishing guns and knives, and teenage boys were breaking bottles so that they would have weapons in their hands.Inside, King found his wife and daughter alive and unharmed. Then he returned to his broken front porch, and, Branch writes,

Holding up his hand for silence, he tried to still the anger by speaking with an exaggerated peacefulness in his voice. Everything was all right, he said. "Don't get panicky. Don't do anything panicky. Don't get your weapons. If you have weapons, take them home. He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword. Remember that is what Jesus said. We are not advocating violence. We want to love our enemies. I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them. This is what we must live by. We must meet hate with love." By then the crowd of several hundred people had quieted to silence, and feeling welled up in King to an oration. "I did not start this boycott," he said. "I was asked by you to serve as your spokesman. I want it to be known the length and breadth of this land that if I am stopped, this movement will not stop. If I am stopped, our work will not stop. For what we are doing is right. What we are doing is just. And God is with us."In the just world that King envisioned, and worked so hard and gave his life trying to bring into being, he would have been eighty-three now.

In the just world that King envisioned, Emmett Till would have been seventy-one today.

Monday, July 23, 2012

In the blaze of midsummer, autumn beckons

{Photos by rocketlass.}

{Photos by rocketlass.}I have a gift for contentment. The moments are relatively rare when I'm looking ahead or behind, willing myself not to be where I am and doing what I'm doing. The grass is almost never greener. There is always the risk that such a tendency will turn pathological, inertia metastasizing, but on on a day-to-day basis it's far from a bad platform on which to build a life.

--

I don't use "gift" casually. I know that my ability to find contentment is in large part a compound of upbringing, habit, and deliberate choice, but it usually feels like more than that, like something given. I've had the wherewithal to take advantage of it, but I didn't earn it in the first place. I've never had even the slightest leanings toward religious belief, but one teaching from Chrsitianity that I have always found useful is the concept of grace--favor not earned but freely given. That's how I feel about my contentment, and I'm grateful.

--

I do, however, have a habit of looking ahead to the next season. Autumn is the favorite, but as it starts to bite I wonder about winter and its snows; winter, lingering, prompts hopes of spring, and spring--along with baseball--brings thoughts of summer nights. Summer, well, until Stahl family vacation in July, it holds its own.

--

My year includes six major holidays: Opening Day, the first day of the playoffs, the first day of the World Series, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and the seven days of the annual Stahl family vacation. Christmas, the chief in this pantheon when I was young, is always on the verge these days of being relegated to the minors, its consumer mania only just balanced by the way it gathers the family and the pleasures offered by its music. If it weren't for Charles Schulz and Vince Guaraldi, it would likely have been stricken long ago.

--

In the introduction to the career-spanning collection of his work Up in the Old Hotel, Joseph Mitchell writes,

I am sure that most of the influences responsible for one's cast of mind are too remote and mysterious to be known, but I happen to know a few of the influences responsible for mine. . . . Aunt Annie would lead us to the cemetery, and there she would pause at a grave and tell us about the man or woman down below. At some of the graves my mother and my Aunt Mary would chime in, but Aunt Annie did most of the talking. "This man buried here," she would say, "was a cousin of ours, and he was so mean I don't know how his family stood him. And this man here," she would continue, moving along a few steps, "was so good I don't know how his family stood him." And then she would become more specific. Some of the things she told us were horrifying and some were horrifyingly funny.--

Up in the Old Hotel, it astonishes me to realize, was published twenty years ago next month. Joseph Mitchell, though he hadn't published a word for nearly thirty years, was still with us then.

--

Last week was the eleventh year of the annual Stahl family vacation. We always traveled in the summer when my sister and brother and I were kids--sometimes my father would come home one day and say that he and his father had finished their work on the farm and thus the next two weeks looked clear, and we'd be away the next day. As we grew up and, serially, went to college, the vacation fell away, victim to the scheduling problems that plague all family endeavors. But soon after she had her first child, my sister--wanting, I think, for her son and his siblings and cousins (all then merely prospective) to know his aunts and uncles and cousins better than we'd known ours--convinced us to give a new, different family vacation a try. Ever since, we've been renting a house for a week in July every year.

--

A few years ago in June I had a dream in which I woke up to discover that it was Thursday of Stahl family vacation week and that I'd somehow piddled away the majority of the week, not in the comfortable, companionable way that is the essence of vacation--which, without effort or plan, draws you closer to family--but in the frenzied, forgettable, workplace-like way of the Wordsworthian admonition:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,The intensity of my relief on realizing it was a mere dream is hard to describe.

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers.

--

With spouses and children, there are twelve of us now, and six years ago we settled, I think for good, on South Haven, Michigan. South Haven is a resort town in a very Midwestern style--there are no fancy restaurants and few places that I trust to pour a martini. Oh, there are shops, but they're selling nothing you need, aside from the used bookstore (where this year I picked up an Anchor paperback of Joseph Conrad's Chance with an Edward Gorey cover). What the South Haven house has to offer is a porch, proximity to the beach, and quiet, and what more could you possibly need?

--

The first few days of vacation found me reading what I think of as the Inexhaustibles: enjoying another of the hundred-plus volumes on the Donald Westlake bookshelf and two of Rex Stout's seventy-three Nero Wolfes. Consumed at a comfortable pace, the works of these authors--to whose ranks could be added P. G. Wodehouse--will see a reader through decades of lazy vacations. Their comforts feel endless.

--

One of the Stouts I read, Over My Dead Body (1940), introduces Nero Wolfe's daughter, which is a shock if for no other reason than that Wolfe has assembled such a complete proxy family in his brownstone on 35th Street. And an actual daughter introduces the troubling concepts of time and age, both banished from Stout's universe--a not insubstantial part of the pleasure of Wolfe, Archie, Fritz, Saul, et al. is that their selves and relationships are fixed, subject to none of the cruelties of change, age, and loss. Time will not, to twist William Maxwell's phrase, darken them.

--

The week was hot, unusually so, and in a twelve-person house the air conditioning is necessarily regulated by the most sensitive of the group. But Wednesday night rocketlass decided to open our bedroom window, affording entry to an illicit breath of outside air . . . and soon after midnight her incorrigibility was rewarded by the unmediated power of a thunderclap, followed by a hard rain, the first this parched shore had seen in months. It poured, satisfyingly, all night.

--

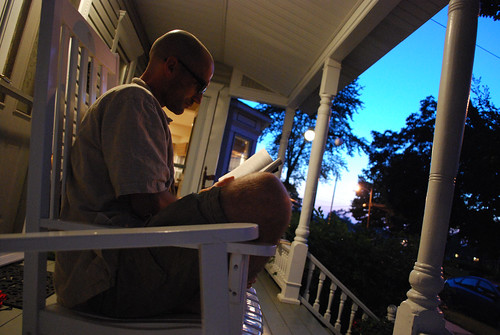

In any gathering, I'm always the first up in the morning. As Norman Maclean puts it, "I get up early to observe the commandment observed by only some of us--to arise early to see as much of the Lord's daylight as is given to us." The morning after the thunderstorm, I woke to a gentle, drumming afterthought of a rain and took my coffee to the porch a good hour before even the two-year-old would be likely to wake. With me I carried W. G. Sebald's The Emigrants (1992). The newly cool, moist air rippled on the skin the way it does in the earliest days of autumn.

--

I'd read Sebald before and not been convinced. It was in 2000, and I was newly entered into a job that has become a career, newly moved to a condo that has become a home, and about to begin a marriage that has become life itself. Sebald's melancholy was not what I was looking for or needed, and I didn't respond to it. But that Thursday morning last week, half of vacation behind me, an unexpectedly autumnal feel in the air, Sebald's words met me at the right time and place, and I sank into his stories of loss and doomed attempts to recover what is forever gone.

--

"When I think back to those days," one of Sebald's characters writes, "I see shades of blue everywhere -- a single empty space, stretching out into the twilight of late afternoon, crisscrossed by the tracks of ice-skaters long vanished."

--

Autumn is for re-reading, and in particular for re-reading books about loss and regret. So I turn again to Norman Maclean's A River Runs through It and Sarah Orne Jewett's The Country of the Pointed Firs, V. S. Naipaul's The Enigma of Arrival, and William Maxwell, all of William Maxwell. I doubt I'll ever stop re-reading those books.

--

Jewett writes, "There was a silence in the schoolhouse, but we could hear the noise of the water on a beach below. It sounded like the strange warning wave that gives notice of the turn of the tide." Mary Poppins, remember, promises to stay until the wind changes. Seasons, however we spot them or define them, are important.

--

I am regularly surprised, returning to A River Runs through It, by how conversational and wry it is, the way that Maclean's narrator--Maclean, in other words--cocoons the wound at the book's center in casual observation, self-deprecating wit, and ironic folksiness, the better to enable it to emerge, beautiful as it is painful, when the time comes to turn our gaze full upon it. Away from the book, we remember its pain and the beautifully rendered prose of its emotional swells; back with it again we are reminded that it's more like life itself than that memory would have us think, prosaic and silly and funny and even a bit vulgar.

--

In A River Runs through It, Maclean's narrator talks with his wife after he's returned her ne'er-do-well brother, sunburned and hungover, from an ill-fated fishing trip, and the subtext of the conversation is his own troubled brother:

"I am trying to help someone," she said. "Someone in my family. Don't you understand?"Grace is a shade of fortune, and when I think of it--unearned in the face of the world's misery--I feel even more grateful. We've not thus far needed, in our family, the help that Maclean's brother needed and couldn't find a way to accept, so our vacations together are peaceful and comfortable and happy. These are the people I am easiest with in all the world.

I said, "I should understand."

"I am not able to help," she said.

"I should understand that, too," I said.

--

I read Sebald Thursday and Friday, and Saturday came and we packed up amid happy tears. The calendar turns, and we look ahead to next year. It's not unreasonable to think that we have decades of these vacations ahead of us, and I hold to that thought.

--

It was 93 degrees today in Chicago, but the days are drawing in and, Stahl vacation behind, autumn beckons.

--

"Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it."

Friday, July 20, 2012

The Johns Steinbeck and O'Hara

Since John Steinbeck's name popped up here not long ago (in a passage from a letter by George Lyttelton slagging one of his lesser efforts, The Wayward Bus), I'll close this recent run of quotes from John Sutherland's Lives of the Novelists with a look at his entry for Steinbeck. Sutherland's biographical sketch is fairly dismissive, essentially agreeing with Fitzgerald's characterization of Steinbeck as a "rather cagey cribber." In his middle period he cribbed from Hemingway, whom he met one time, in the early 1940s:

I'm inclined to give Steinbeck a tad more credit than Sutherland. Of Mice and Men is simple but moving, and East of Eden, while stagey in places and a tad overblown throughout, is nevertheless powerful. The Red Pony and The Pearl, on the other hand, those staples of middle-school curricula, are horrid and have probably done as much to destroy a love of reading as handheld video games.

Sutherland does at least let Steinbeck off more easily than the aforementioned John O'Hara. O'Hara gets more credit for his best work--Sutherland praises Appointment in Samarra, though he neglects to mention the great novellas of the early 1960s--but as a man he comes in for harsh judgment. In contrast with John Hersey, whose bio precedes O'Hara's, Sutherland writes,

John Hersey, who set it up, records that the occasion was a "disaster." Steinbeck had given fellow novelist John O'Hara a blackthorn stick. Hemingway grabbed the stick from O'Hara and broke it over his own head and threw the pieces on the ground, claiming it was a "fake of some kind." Drink was probably behind his actions, but one is tempted to allegorise the episode as Hemingway protesting Steinbeck's appropriation of "his" style. That is how Steinbeck read the event, at least. According to Hersey, "Steinbeck never liked Hemingway after that--not as a man."With O'Hara and Hemingway involved in an altercation, I think it's safe to say that, yes, drink played a part.

I'm inclined to give Steinbeck a tad more credit than Sutherland. Of Mice and Men is simple but moving, and East of Eden, while stagey in places and a tad overblown throughout, is nevertheless powerful. The Red Pony and The Pearl, on the other hand, those staples of middle-school curricula, are horrid and have probably done as much to destroy a love of reading as handheld video games.

Sutherland does at least let Steinbeck off more easily than the aforementioned John O'Hara. O'Hara gets more credit for his best work--Sutherland praises Appointment in Samarra, though he neglects to mention the great novellas of the early 1960s--but as a man he comes in for harsh judgment. In contrast with John Hersey, whose bio precedes O'Hara's, Sutherland writes,

Stylish decency was never the calling card of John O'Hara. Words like "oaf," "lout," and "brute" attach themselves to him, particularly in his drinking days. "A strange, unpleasant man," one critic calls him. Paul Douglas, the Hollywood star, once grabbed O'Hara by his necktie and made a good attempt at throttling him, after an especially obnoxious piece of drunkenness. Many wished Douglas had succeeded.And that's all with Sutherland leaving out my favorite O'Hara story, of the time he greeted a friend for lunch while wearing no pants . . . which wasn't even his worst offense of the day. But the point is made: O'Hara was a writer better encountered on the page than over a drink.

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

Roald Dahl and Kingsley Amis

One of the many interesting meetings featured in Craig Brown's One on One that I'd not previously heard of is between Kingsley Amis and Roald Dahl, who met at a party thrown by Tom Stoppard in 1972. Craig tells how, thrown together by chance with Amis, Dahl professes himself a big fan, then starts asking about money:

But good god, imagine what a children's book by Kingsley Amis would have been like. Ghastly to think about, isn't it?

"So you've no financial problems."Dahl, frustrated, cuts to the chase: "What you want to do is write a children's book. That's where the money is today, believe me." Amis, knowing his limitations, demurs:

"I wouldn't say that either, exactly, but I seem to be able to . . ."

"I couldn't do it," says Amis. "I don't think I enjoyed children's books much when I was a child myself. I've got not feeling for that kind of thing."The story is told, both by Amis in his memoirs and by Brown in his book, as a sort of inadvertent revelation by Dahl of a calculating cynicism, and that's certainly how it would seem if it ended there. But Brown relates the conversation's conclusion, which to my eye changes its whole tone:

"Never mind," replies Dahl. "The little bastards'd swallow it."

In his account, Amis goes on to say that children are meant to be good at detecting insincerity, and would probably see through him. . . .That apparently sincere sentiment complicates the anecdote, and, moreover, when its sincerity about hard work and commitment is combined with the bluntness of his earlier statement, seems to represent the Dahl we know.

"Well, it's up to you. Either you will or you won't. Write a children's book, I mean. But if you do decide to have a crack, let me give you one warning. Unless you put everything you've got into it, unless you write it from the heart, the kids'll have no use for it. They'll see you're having them on. And just let me tell you from experience that there's nothing kids hate more than that. They won't give you a second chance either. You'll have had it for good as far as they're concerned. Just you bear that in mind as a word of friendly advice."

But good god, imagine what a children's book by Kingsley Amis would have been like. Ghastly to think about, isn't it?

Labels:

Craig Brown,

Kingsley Amis,

One on One,

Roald Dahl

Monday, July 16, 2012

Branwell Bronte

I wrote last week about John Sutherland's Lives of the Novelists, and today I'll share a passage that demonstrates Sutherland's gift for concision. It comes from his group portrait of the Brontes:

That said, at this late date what's the worst charge that can be laid at Branwell Bronte's door? The fact that his alcoholism--and, presumably, the hope of his sister that being confronted with its horrors might force him to deal with it--led Anne Bronte to ruin The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, a book that opens with a gloriously ominous and intriguing setting of scene and character . . . then rapidly devolves into a dull-as-dirt temperance novel.

At this point, in 1843, Anne's career crossed, fatefully, with that of her brother. Branwell, having failed to get the hoped for place at university, went on to fail as a portrait painter. Even more catastrophic was his being dismissed from a clerical job with the local railway firm under the suspicion of embezzlement. Despite his known dissipations, Anne secured for him a tutor's position with her own employers, the Robinsons. Branwell was dismissed from that post for "proceedings . . . bad beyond expression"--namely misconduct (vaguely specified) with Mrs Robinson. Mr Robinson threatened to shoot him. On his dismissal in 1845 he fell into a "spiral of despair" which he medicated with opium and alcohol.Is there any figure on the periphery of literature more sadly useless than Branwell Bronte? That's not to say one doesn't have sympathy for him--being an alcoholic is far from easy, an alcoholic Bronte even more difficult--but all the same his chance at being a tragic figure is undone by his uncanny ability to fail at everything, usually in the most disreputable available fashion. A tragic figure must, I think, have some promise left sadly unfulfilled, no?

That said, at this late date what's the worst charge that can be laid at Branwell Bronte's door? The fact that his alcoholism--and, presumably, the hope of his sister that being confronted with its horrors might force him to deal with it--led Anne Bronte to ruin The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, a book that opens with a gloriously ominous and intriguing setting of scene and character . . . then rapidly devolves into a dull-as-dirt temperance novel.

Friday, July 13, 2012

The gossipy bits of literary biography

I'm still scrambling a bit to stay on a reasonable blogging pace amid the demands of work and travel, so the next few days will likely see me simply sharing some passages from two books that have been my regular companions for the first half of this year, Craig Brown's One on One and John Sutherland's Lives of the Novelists. I've written already about both; suffice it to say that if, like me, you enjoy the gossipy bits of literary biography, you should have these books on your shelves. (For a more in-depth consideration of Sutherland's book, you can't do much better than this post from Open Letters Monthly, which addresses the book's weaknesses as well as its obvious strengths--and offers the added bonus of Sutherland himself responding in the comments.)

The pleasure of Sutherland's book lie largely in its scope--the sheer number of eminently forgettable authors whose oeuvre he's apparently read is astonishing. (Of forgotten American hack J. H. Ingraham Sutherland writes, "The most interesting novel of his third, holy phase is The Sunny South.") Then there are his pithy turns of phrase. Of Poe he writes,

Brown's book, meanwhile, follows a daisy chain of chance encounters between writers, artists, and other cultural and historical figures from the nineteenth century to the present. Dozen of old favorites turn up in its pages, including Tolstoy, Raymond Chandler, Mark Twain, and many more, but the scene that has remained most vivid in my mind these many months is from a chance meeting between Evelyn Waugh and Alec Guinness in 1955. They're both at St. Ignatius chapel to witness the confirmation of Waugh's god-daughter, Edith Sitwell, and they're joined by, in Waugh's words, "an old deaf woman with dyed hair," who, according to Brown, "walks unsteadily with the aid of two sticks." Her "bare arms are encased in metal bangles which give [Guinness] the impression that she is some ancient warrior."

In attempting to sit, she falls, and her bangles go flying:

The pleasure of Sutherland's book lie largely in its scope--the sheer number of eminently forgettable authors whose oeuvre he's apparently read is astonishing. (Of forgotten American hack J. H. Ingraham Sutherland writes, "The most interesting novel of his third, holy phase is The Sunny South.") Then there are his pithy turns of phrase. Of Poe he writes,

The skull on the desk, that standard Ignatian aid to meditation, is common enough in literature. With Poe, the warm flesh is still slithering off the bone.and

It was the pattern of his life to succeed brilliantly, then move on before getting bogged down in the consequences of his own brilliance. If necessary he would drink himself out of the sinecures friends were willing to set up for him.Of Mark Twain, he writes,

Mark Twain, we may say, made American literature talk--unlike, say, Henry James, who merely made it write.Melville, in the midst of a full entry, elicits this eye-popping sentence about his seafaring years,

Communal onanism was called "claw for claw"--sailors going at each other's privates like fighting cocks.Of Anne Bronte he writes,

Anne survived her brother by only a few months, dying decently, but tragically early, of the family complaint. One imagines she met her end more dutifully.And of Emily,

Emily is the most enigmatic of the writing sisters. No clear image of her remarkable personality can be formed. Branwell sneered at her as "lean and scant" aged sixteen. She, famously, counselled that he should be "whipped" for his malefactions. She evidently thought well of the whip and used it, as Mrs Gaskell records, on her faithful hound, Keeper, when he dared to lie on her bed. A tawny beast with a "roar like a lion," Keeper followed his mistress's coffin to the grave and, for nights thereafter, moaned outside her bedroom door.Readers, this book is for you.

Brown's book, meanwhile, follows a daisy chain of chance encounters between writers, artists, and other cultural and historical figures from the nineteenth century to the present. Dozen of old favorites turn up in its pages, including Tolstoy, Raymond Chandler, Mark Twain, and many more, but the scene that has remained most vivid in my mind these many months is from a chance meeting between Evelyn Waugh and Alec Guinness in 1955. They're both at St. Ignatius chapel to witness the confirmation of Waugh's god-daughter, Edith Sitwell, and they're joined by, in Waugh's words, "an old deaf woman with dyed hair," who, according to Brown, "walks unsteadily with the aid of two sticks." Her "bare arms are encased in metal bangles which give [Guinness] the impression that she is some ancient warrior."

In attempting to sit, she falls, and her bangles go flying:

"My jewels!" she cries. "Please to bring back my jewels!"That story rivals the story of Guinness's premonitory warning to James Dean--also included in Brown's book--as the best Alec Guinness story I know.

Waugh and Guinness dutifully get down on all fours and wriggle their way under the pews and around the candle sconces, trying to retrieve "everything round and glittering."

"How many jewels were you wearing?" Waugh asks the old deaf woman.

"Seventy," she replies.

Under the pews, Waugh whispers to Guinness, "What nationality?"

"Russian, at a guess," says Guinness, sliding on his stomach beneath a pew and dirtying his smart suit.

"Or Rumanian," says Waugh. "She crossed herself backwards. She may be a Maronite Christian, in which case beware."

The two men start laughing, and soon, according to Guinness, get "barely controllable hysterics." They pick up all the bangles they can find. Guinness counts them into her hands, but the old deaf woman looks suspiciously at the pair of them, as if they might have pocketed a few.

"Is that all?" she asks.

"Sixty-eight," says Guinness.

"You are still wearing two," observes Waugh.

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Alice Thomas Ellis, Penelope Fitzgerald, and more

In the comments to my recent post on Alice Thomas Ellis, reader zmkc left a link to a post she'd written about Ellis's husband, Colin Haycraft, an editor who was at least in part responsible for shepherding not only Ellis, but also Penelope Fitzgerald and Beryl Bainbridge into print.

If you enjoy any of those writers, zmkc's post is well worth checking out. Along with some delicious quotations from one of Ellis's novels, she also reflects on the pleasures afforded by the brevity of the work of all three women:

As for Alice Thomas Ellis, I'm sure you'll be hearing more from me soon--I'm waiting impatiently for the Chicago Public Library to dig up copies of a couple more of her novels.

If you enjoy any of those writers, zmkc's post is well worth checking out. Along with some delicious quotations from one of Ellis's novels, she also reflects on the pleasures afforded by the brevity of the work of all three women:

As well as providing us with the pleasure of Bainbridge, Fitzgerald and Ellis's writing, Haycraft also argued in defence of the short novel (apparently, he wrote something called 'a satire' on the subject for the Times Literary Supplement, but, as it was well before the advent of the internet, I can find no trace of it). I support that view, not because I don't enjoy Dickens or George Eliot or Tolstoy, but because I think the lengthy novels that are published nowadays are rarely up to the standard of their predecessors. Nowadays they are often really just sloppily edited - or completely unedited - short novels (there's a slim volume lurking inside every fat volume, or something like that).Oh, and there's a bonus of some A. N. Wilson-bashing, a pastime I always enjoy. Much as I appreciate his biography of Tolstoy and his book on the Victorians, I feel he's still got a ways to go before he's fully paid out for the jaw-dropping mean-spirited pettiness of his memoir of his friendship with Iris Murdoch and John Bayley.

As for Alice Thomas Ellis, I'm sure you'll be hearing more from me soon--I'm waiting impatiently for the Chicago Public Library to dig up copies of a couple more of her novels.

Monday, July 09, 2012

Wilkie Collins meets a reader

Peter Ackroyd's brief life of Wilkie Collins, while disappointingly thin on gossipy speculations about Collins's seedier aspect--his two households, his opium addiction--does offer plenty of anecdotal nuggets to enjoy, of which the following is easily my favorite. Soon after the publication of his novel of a reformed prostitute, The New Magdalen, Collins took a trip on a train and shared a car with a clergyman and his two daughters. Ackroyd writes,

But it's more fun to believe it, so let's. And let's also be grateful that Collins wasn't traveling in Japan, where people wrap their books in brown covers, or in the future, where all e-readers present the same anonymous face.

When the clergyman fell asleep one of the young ladies quietly took out a book from her bag; she dropped it and, when Collins retrieved it for her he saw that it was The New Magdalen. She blushed as she realised that her secret reading was discovered. "It's perfectly dreadful," she told her sister. But soon enough she was thoroughly absorbed in it. On signs that her father was about to wake, she quickly returned the book to her bag. When Collins looked at her, she blushed again.It's a charming little story, almost too perfect to believe, like the story (for which I can't this morning find a reference) that Dickens overheard a reader in a shop asking for the next number of his current book and from that realized just how far behind he'd allowed himself to fall--at which point he raced home and set to work.

But it's more fun to believe it, so let's. And let's also be grateful that Collins wasn't traveling in Japan, where people wrap their books in brown covers, or in the future, where all e-readers present the same anonymous face.

Thursday, July 05, 2012

Wilkie Collins loves America

Just after finishing Wednesday's post, I came across a bit that seems worth sharing as an addendum and counter to all the British anti-Americanism I included in that post. Peter Ackroyd, in his brief life of Wilkie Collins, writes of Collins's 1873 tour of America,

Collins's approbation stands in contradistinction to what his friend Dickens found in America. Upset by, among other things, the Americans' refusal to legislate and enforce copyrights--and what he saw as their disregard for his losses therefrom--he turned his American Notes for General Circulation into a savage indictment of the whole people. Much of the book's criticism is marred by spleen, and thus rendered not wholly convincing, but the following passage, at least, from the conclusion, describes an American trait that's certainly still with us:

[H]e was generally beguiled and charmed by the Americans whom he met. They were frank, cheerful, and free; they did not obey the conventions of Victorian England that Collins himself cordially detested. They lacked the hypocrisy and frigid good manners of the English middle class. They had minor failings, however; they did not hum or whistle; they did not keep dogs; and they never walked anywhere.Good to know that the American aversion to non-mall walking has been around for more than a century. Collins would surely be pleased by the spread of dog ownership, however, though I don't know that we whistle or hum any more now than we did then.

Collins's approbation stands in contradistinction to what his friend Dickens found in America. Upset by, among other things, the Americans' refusal to legislate and enforce copyrights--and what he saw as their disregard for his losses therefrom--he turned his American Notes for General Circulation into a savage indictment of the whole people. Much of the book's criticism is marred by spleen, and thus rendered not wholly convincing, but the following passage, at least, from the conclusion, describes an American trait that's certainly still with us:

The merits of a broken speculation, or a bankruptcy, or of a successful scoundrel, are not gauged by its or his observance of the golden rule, "Do as you would be done by," but are considered with reference to their smartness. I recollect on both occasions of our passing that ill fated Cairo on the Mississippi, remarking on the bad effects such gross deceits must have when they exploded, in generating a want of confidence abroad, and discouraging foreign investment: but I was given to understand that this was a very smart scheme by which a deal of money had been made: and that its smartest feature was that they forgot these things abroad, in a very short time, and speculated again, as freely as ever.However, since we're but little removed from Independence Day--as evidenced by periodic explosions outside--I'll let Collins's appreciation be the last word on the subject today. Ackroyd writes,

[H]e had thoroughly enjoyed the experience; he had made new friends and had enjoyed the unaffected admiration of his audiences. "The enthusiasm and kindness are really and truly beyond description," he wrote. "I should be the most ungrateful man living if I had any other than the highest opinion of the American people."And now to go whistle "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" in Collins's honor.

Tuesday, July 03, 2012

Birthday wishes

I suspect that the fact of my being an American is a lot like the fact of my being male: it affords me almost incalculable unearned privilege, and, while I can (and do try to) think about it and analyze the way that it plays, subconsciously and overtly, into my thoughts and feelings and assumptions--most likely into all of them--and thereby gain some distance from and knowledge of the essence of that identity, at the same time the distance will never be such that I can say, definitively, "This is what it is like to be an American," or still less, "This is what it would be like not to be an American."

Anglophilia and analysis only take you so far, the former because, really?, the latter because rational analysis cannot always chase out such deeply woven currents of being.

So for my nation's birthday, I offer some disjointed recent gleanings to accompany the delightfully ridiculous weeklong orgy of explosives in which my neighborhood annually indulges.

First, I'll draw on a letter sent by John Keats in October 1818 to his brother and sister-in-law, George and Georgiana Keats, then resident in Louisville, Kentucky:

Dilke, whom you know to be a Godwin perfectibility man, pleases himself with the idea that America will be the country to take up the human intellect where England leaves off--I differ with him greatly. A country like the United States, whose greatest Men are Franklins and Washingtons, will never do that. They are great Men, doubtless, but how are they to be compared to those our countrymen Milton and the two Sydneys? The one is a philosophical Quaker full of mean and thrifty maxims, the other sold the very Charger who had taken him through all his battles. Those Americans are great, but they are not the sublime Man--the humanity of the United States can never reach the sublime.Oh, how much one could disagree with Keats about Franklin! Washington, fine: impressive, great, a man for whose sense of duty it's impossible not to be grateful--but at the same time always coming across as emotionally and intellectually a bit flat. Jefferson you can wrangle with, Hamilton you can joust with, Lincoln--well, it's best we not derail this with my love of Lincoln. Washington you are stuck simply admiring.

But Franklin? All the smallness and greatness of humanity in one package, endlessly inventive and endlessly humane, beguiled by the ladies, in love with France, distracted almost in almost exactly inverse proportion to the direct discipline of his maxims, embodying in his pot-bellied person the linchpin of American democracy. Oh, how not to love Franklin?

As for the sublime . . is it wrong of me to think that, at a minimum, the late Donna Summer achieved it around minute ten of a couple of her greatest disco anthems?

But in general one can't quite trust the English on the subject, can one? George III would be proud of what Jessica Mitford reports in this letter, sent on August 8, 1959 from London to civil rights activist Marge Franz:

One rather noticeable thing is the solid anti-Americanism of all sections of the population, rich & poor, right & left. I've yet to meet one person who has the least desire to go to America, or one who has been there & liked it. It is a queer mixture of ordinary English chauvinism, snobbishness, intellectual snobbishness, & disapproval of American policies. Rather well worth analyzing & cataloguing, it might make a good article. . . . Madeau Stewart, 35 year old executive at BBC, no doubt solid conservative: "Aren't Americans awfully ignorant on the whole? Don't you find it depressing not having anyone to talk to?"Mitford's take on the attitude of the English in the Eisenhower years is corroborated by this passage from a letter sent by George Lyttelton to Rupert Hart-Davis on May 15, 1957:

It is all wrong, I know, but I cannot ever take Americans quite seriously--I mean their tastes and judgments and values, though now and then one strikes an absolutely Class I man, e. g. the late Judge Wendell Holmes. But either I always have bad luck with their novelists, or I just don't know my way about. I remember liking Steinbeck's first best-seller, but last week, seeing his name, I wasted half-a-crown on his The Wayward Bus to read in the train. Not a single character who was not either loathsome or silly.As someone who works in publishing--and buys a ridiculous number of books--I can't help but apply Keats's epithet for Franklin's maxims, "mean," to anyone well-situated who laments the cost of a disappointing book. The time wasted, certainly, but the cost?

That said, the marketing person in me can't help but be amused by what follows:

The blurb calls it a ruthless picture, showing what people are really like, i.e. all in need of an ounce of civet. Is the whole of U.S.A. thinking of nothing but the female bosom?An understandable question, but the answer is no: even then, there was Ray Bradbury, among the least sex-obsessed of novelists, who in his Paris Review interview said,

I like to think of myself going across America at midnight, conversing with my favorite authors.And then there's the sublimity--unquestionable, I say--of this exchange, overheard at Mineta San Jose International Airport (ah, Mineta, a Japanese-American reminder of America's gloriously diverse essence) on Monday:

TODDLERAnd finally . . . well, you didn't believe me earlier when I said I would leave Lincoln out of this, did you? From the glory that is the First Inaugural:

Making gestures representing an explosion

Boom! Boom!

DAD

Stop it.

TODDLER

Boom! Boom! BOOM!

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.Good god, I love that man. Enjoy the holiday, fellow patriots. Watch out for explosions, ye better angels.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)