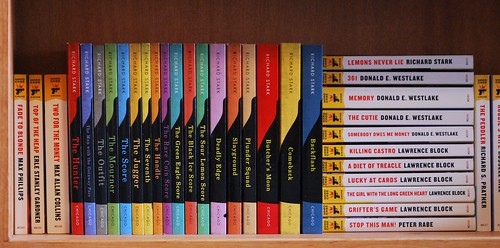

{Photo by Flickr user Dunechaser. Used under a Creative Commons license, which reserves some rights.}

Geoff Dyer's The Missing of the Somme (1994) has just been published in the States for the first time, the lag probably an indication less of Dyer's formerly low profile over here than of the relatively small place of World War I in American memory. I suspect that if, rather than World War I, we called it the Second Franco-Prussian War--thus stripping it of its not inaccurate position as a prelude to World War II, which remains a constant topic of self-congratulatory (and, again, not wholly inaccurate) American reflection--it would occupy a position more like the French and Indian War or the War of 1812, covered in grade school, then all but forgotten by anyone who's not a history buff.

For our participation in that war was late and limited, our losses negligible. And by 1914, we were just settling into what would become a century and a half (so far) of reflection on our own horrible, romantic, inescapable, endlessly compelling war, the Civil War. Its battlefields were America's Somme, its convulsions and aftermath our rending of the veil of heroic illusion. That we, driven by Southern apologists, spent much of the twentieth century attempting to sugarcoat it, strip it of its meaning, and accord both sides equal honor despite the fact that one side was fighting to keep humans in bondage seems fundamentally American, a core sample of our national character.

No, for us the impact of World War I was relatively limited at the time, attenuated nearly to nothingness by now. Its greatest effect was to continue and amplify the consolidation of federal power, regularization of daily life, and knitting together of the many disparate and rural pockets of the far-flung nation that was set into motion by the vast apparatus of the Civil War and that reached its apogee during World War II. (One example: in his wonderful, data-based Daily Life in the United States, 1920–1940, David E. Kyvig notes that nearly one-third of American draftees for World War I were rejected as physically unfit, leading to significant pushes by the federal government to educate the population about proper nutrition, exercise, and hygiene.) The emotional valence of the war has never come close to what it carries for European nations.

And therein lies the fascination for me, and the reason that Dyer's book seems nearly perfect. It is an account, not of the war, but of how Europeans (and the English in particular) have remembered it--beginning with poems, news accounts, and memorials created as it was happening and carrying through to the moments when Dyer and friends, sometimes a bit drunk, trek from battlefield to battlefield in 1990s France. It owes an acknowledged debt to John Berger; its closest other kin is probably Paul Fussell's magnificent The Great War and Modern Memory, on which it draws--though Dyer writes much more personally and is much more open to the idea, and its accompanying frustration, that certain questions, certain feelings, certain, to steal from Berger, ways of seeing, have been closed to us by time. Its closest Stateside kin, which I hope Dyer knows, is Lee Sandlin's Losing the War, published in the Chicago Reader in 1997. All three are less concerned with facts--though they don't disdain them--than with impressions, reactions than actions.

In a book full of interesting ideas and observations, the sort that lead a reader down new paths of thought and inquiry, this passage stood out:

"Before the Great War there was no war poetry as we now conceive the term," writes Peter Parker in The Old Lie; "instead there was martial verse." So pervasive were the conventions of feeling produced by this tradition that in 1914 the eleven-year-old Eric Blair could write a heartfelt poem--"Awake, young men of England"--relying entirely on received sentiments. In exactly the same way, an eleven-year-old writing fifty years on could, in similar circumstances, come up with a heartfelt poem expressing the horror of war--while also relying solely on received sentiment. In some ways, then, we talk of the horror of war as instinctively and enthusiastically as Rupert Brooke and his contemporaries jumped at the chance of war "like swimmers into cleanness leaping." This is not just a linguistic quibble. Off-the-peg formulae free you from thinking for yourself about what is being said. Whenever words are bandied about automatically and easily, their meaning is in the process of leaking away or evaporating. The ease with which Rupert Brooke coined his "think only this of me" heroics by embracing a ready-made formula of feeling should alert us to--and make us sceptical of--the ease with which these sentiments havebeen overruled by another.Dyer's skepticism, here and throughout, is bracing, in a way that goes far beyond the question of World War I and its meaning. We should always keep in mind the seductive danger of received opinion; when everyone is agreeing with us we should pause a moment to disagree with ourselves and see how that sits. Dyer reminds us that even the writing of participants in the war traffic in tropes that were common enough to be limiting thought and expression, closing off rather than opening out questions, as the war was just getting underway. He doesn't dismiss the war poems and memoirs, but he reminds us that even though those who experienced the war had to wrestle it into shape somehow, and--to no discredit--they often chose the shapes that were, culturally speaking, lying around.

In some sense, though he doesn't mention him by name, Dyer seems to endorse Ford Madox Ford's take on the war: Ford's masterpiece, the four-volume Parade's End, is almost entirely concerned with the war and its damage; by the third volume, description has largely given way to ellipses, elision indicating that which, if described, would killingly concretize into cliche.

Yet at the same time Dyer's account can't help but send us back to that generation in general and its literary output. If we try to escape the frame of "horror," and focus instead--as I find myself doing--on the slightly narrower question of what must that all have been like (which ranges from what must it have been like to winter in the trenches; to what must it have been like to live, a woman, in a village from which all the men had left; to what it must have been like to live in a nation in which one in ten males has been violently killed), we have to return to Graves and Sassoon and Owen (and even, in a refracted way, Lord Dunsanay, whose Tales of War (1918), recently republished by Whisky Priest Books, offers a simultaneously more literary and more vigorously angry perspective). They remain our strongest link to those irrecoverable times and emotions, and as the centennial of the tragedy approaches, they have lost little of their power. I suspect our descendants will still be wrestling with them at the bicentennial.