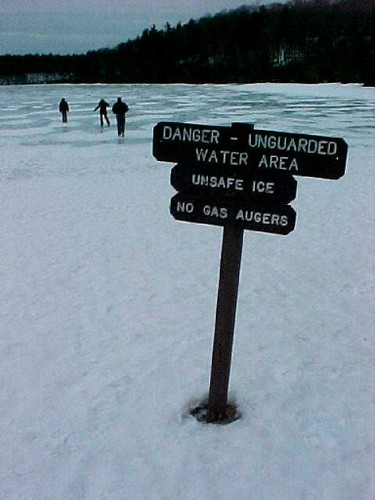

{Photo by rocketlass.}

Just in time for a game of Risk with my nephew, his dad, and my brother*, over Christmas weekend I started reading Rites of Peace: The Fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna (2007), by Adam Zamoyski. At the halfway mark, it’s nearly as fascinating as Zamoyki’s earlier book, Moscow 1812.

Zamoyski does a remarkable job of helping the reader keep the dizzying array of people and interests at the Congress straight. Though not representative of his general style, the following list is worth reproducing for the picture it gives of the complexity of Napoleonic-era European politics; it covers only the minor German interests--dispossessed nobles and the like--in attendance at the Congress:

Some Standesherren had got together and elected one of their number in a region; others preferred to go themselves. There were also representatives of the four Hanseatic cities (Hamburg, Lubeck, Bremen and Frankfurt); of the city of Mainz; of the Chamber of Commerce of the city of Mainz; of the Teutonic Order; of the firms of Bonte and Co., Kayser and Co. and Wittersheim and Bock, creditors of the government of Westphalia, which had been abolished; of the Bishop of Liege; of the subjects of Count Solms-Braunfels. One delegation of Catholic clergy demanded full restitution under Papal authority; another, consisting of four delegates led by the Bishop of Constance, called for the institution of a new German national Catholic Church. The Pope’s delegate, Cardinal Consalvi, was there to oppose this. There was also a delegation, consisting of Friedrich Justin Bertuch of Weimar and Johann George von Cotta of Stuttgart, publisher of the Allgemeine Zeitung, representing eighty-one German publishers and demanding a copyright law as well as freedom of the press. And there were J. J. Gumprecht and Jakob Baruch of Frankfurt and Carl August Buchholz of Lubeck, representing the interests of the Jews. They were one of the few groups eager to preserve changes made by Napoleon, who had granted them full equality, of which the authorities in many German states were now attempting to strip them once more.Whew.

Yet out of this mess, Zamoyski constructs a narrative that is clear, coherent, and, even more remarkable, compelling. He freely indulges a taste for entertaining anecdotes--as in this story of one of the English plenipotentiary Sir Charles Stewart:

Accident-prone as ever, he came home one evening in his usual drunken state, tore off his uniform and threw himself onto the bed without bothering to close the french windows into the garden, and woke up to find that not only his richly gold-braided hussar jacket with its diamond-studded decorations, but every single item of clothing had been stolen. He was confined to quarters while a tailor ran up a new uniform.The book spills over with such moments, which together paint a lively and unforgettable picture of the upper reaches of early nineteenth-century life.

Zamoyski is also blessed with the presence of three of the century’s most memorable figures: Tsar Alexander--of whom a friend once wrote,

He would willingly have made everyone free, as long as everyone willingly did what he wanted.--the Austrian foreign minister, Metternich--who

was in every sense the center of his own universe. He would write endlessly about what he had thought, written and done, pointing out, sometimes only for his own benefit, how brilliantly these thoughts, writings, and doings reflected on him. This egotism was buttressed by a monumental complacency that was proof against all experience.--and the French foreign minister, Talleyrand--whom Goethe called "the supreme diplomat of our century." and whom Roberto Calasso in The Ruin of Kasch credited with "the ability to sniff out the age." Together (or more accurately, perpetually at odds) they offer a tableau of drama, intrigue, and personal power that are breathtaking in their contrast to the limited political life of our more democratic age.

I’ll have plenty more to share from this book over the coming weeks, but with New Year’s Eve looming, it seems fitting to close with a brief description of one of the dozens of lavish balls held during the Congress. This account of the opening night fete--which filled two ballrooms and an indoor riding school--comes from the young German wife of the Danish ambassador:

In place of the windows there were enormous mirrors which reflected 100,000 sparkling lights. . . . The stairs swept down in two arcs to the floor of the riding school, which was covered with parquet and ringed on three sides with rows of seats like an amphitheatre. Blinded and almost dizzy, I paused for a few moments at the top of the stairs, and once I had gone down I could view the dazzling procession as the whole court of Vienna and those of other countries descended.Those of you who, like me, tend to be skeptical about parties may find the response of Prussian chancellor Karl August von Hardenberg more in your line:

"Crush," Hardenberg jotted down in his diary. He disliked large gatherings and was in a bad mood besides, but even he could not resist adding "--many beautiful women."Sounds like he might have been the sort to stay home on New Year’s.