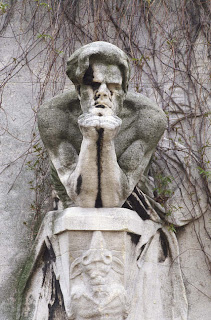

{Charle's Baudelaire's monument in the Cimetiere du Montparnasse.}

In a piece on the decadent writers for the New Yorker from October 1923, collected in the first of the new Library of America volumes, Edmund Wilson writes,

The school which began with Baudelaire and is now dissolving with Arthur Symons derived its principal force from its constant conviction of sin. The decadents talked much about "paganism," but their point of view was not pagan: it was a reaction against Victorian Christianity by people who were still Christians and Victorians. . . . How can you believe that sin is "the good" and at the same time believe it to be sin? From the point of view of the person who is really convinced of the sinfulness both of the pleasures of the flesh and of the play of the intelligence, they are things to be sedulously shunned; from a point of view really pagan, they do not become an issue at all. Baudelaire had to pretend to take the Devil seriously while he was spending his artistic life endeavoring to make him attractive; and his successors followed his example.

Wilson has hit upon the primary problem with rebellion as a position in general: a significant part of the attraction of rebellion is--and, it seems clear, always has been--simply doing what one is not supposed to do. Yet that very pleasure can only occur if one allows that the rules one is breaking have some essential power. What's fun is to realize that Wilson wrote this from the heart of the rebellion that was 1920s Greenwich Village--and that he and his milieu were not even that distant in time from the decadents about whom he was writing. Baudelaire had been long dead, but Aubrey Beardsley, Oscar Wilde, and Paul Verlaine, to take a few, had only died--and thus left off outraging society--twenty-five years or so earlier. When Wilson goes on to write that Baudelaire, like other fin-de-siecle writers, seems diminished now--that we can't read them

with the enthusiasm of their contemporaries. The effectiveness of the subjects dealt with depends on one's being shocked by them, and when the prejudices to be baited have been removed, the works of art are no longer exciting.--an unspoken question lingers: If those artists' creations had, in a sense, been assimilated in such a short time, what clues did that give about the fate of the more outre works--and lives--of Wilson's own contemporaries?

For all his careful contextualization, however, Wilson never goes so far as to outright dismiss Baudelaire. For that, we have to turn to Borges, who, in a letter to his friend Adolfo Bioy Casares, positively erupts on the topic:

It is ridiculous to fill literature with cushions and furniture and show evil in a positive light. Baudelaire helps one gauge whether a person understands anything at all about poetry, whether he is an imbecile or not: anyone who admires Baudelaire is an imbecile.

If Borges is limiting the category of imbecile to people who admire Baudelaire, then I escape easily. But if--as seems likely from the context--by "admire" Borges actually means "enjoy," then an imbecile I am, at least once in a while. I suppose there are worse things to be--like maybe a devil?

No comments:

Post a Comment